Click Above For Home Page

Many people still think of God as a male super-being. Karen Armstrong, once a Catholic nun, and author of A History of God, explains why He isn't.

FORGIVE the literal-minded, perhaps simple-minded, they assume Christianity's god to be male. Masculine pronouns litter the Scriptures; the hirsute face of God--or the Son of God--graces Greek icons and El Greco paintings alike; the most familiar prayer begins, 'Our father, which art in heaven'; and the holy trinity is never defined as 'mother, daughter and holy ghost'.

Indeed, blame the Reformation--at least for Protestants. Ever since the Bible was translated into the vernacular some four centuries ago, it has ceased to be the preserve of clerical cognoscenti. Listening or reading in their own languages, ordinary folks--unsophisticated believers--may see God as a male personality with all the faults and virtues of masculine human beings writ large, or as a cosmic Big Brother, controlling events on earth with absolute power, and demanding absolute obedience. No wonder the modern feminist spies grist for her cause, railing against the idea that a male deity should approve the iniquity of patriarchy and, by identifying the sacred with the masculine, should marginalize women in the religious world. Just possibly (though most Anglicans hotly deny it), the Church of England's bitter dispute over the ordination of women to the priesthood has been fuelled by this conception of God as male. Anglican and Roman Catholic Christians see their priests as representatives of God. So ingrained is the idea of a male God that many are repelled by the notion of their deity being represented by a woman. The problem is exacerbated by the doctrine of the incarnation, which teaches that the Word of God was made flesh and came to live in the world in the person of Jesus of Nazareth. The choice of a male rather than a female body seemed to indicate that God must also--somehow--be like a man.

This, of course, is to regard God in far too reductive a way. When pushed, even the most diehard opponent of women's ordination will admit that since God is spirit and transcends all human categories 'he' cannot be confined to a particular gender. The very first chapter of the Bible says firmly that both male and female human beings were created in God's image (Genesis 1:27); both sexes, therefore, are capable of expressing the mysterious divine essence.

In the same spirit, the Greek Fathers of the Church, who refined (or even defined, given the scanty and ambiguous theology on the subject in the gospels) the doctrine of the incarnation at the Council of Nicaea in 325, did not imagine that the Word of God had become a man in any simplistic way. They stressed the distinction between 'maleness' and 'humanity'. The Word had not become a male human being (in Greek, aner) but had become humanity or Man (anthropos). The doctrine expressed their conviction that the transcendent God was permanently allied with the human race--with the females as well as the males of the species.

The Greek Orthodox theologians, however, suspected that their fellow Christians in Western Europe had a more limited conception of God--namely, that their images of the divine reflected a reality that could be defined like any other philosophical identity. This was anathema to the Greeks, who retained a conviction that all God-talk could only be symbolic, inadequate and provisional. The sacred, the Greeks argued, could never be contained within a human system of thought. So the doctrine of the trinity (never spelled out in detail in the New Testament) was formulated, again in the 4th century, in part to remind Christians that they must not think about God as a simple personality, male or otherwise.

In their devout agnosticism about God's nature, they were far closer to Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist or Hindu thought about the ultimate. Western Christians, who never really felt at ease with the Trinitarian doctrine derived from the Greek Orthodox and who believed that it was possible to define God, were thus steering against the tide.

This western literalism increased with the advent of modern science. Many Europeans and Americans now assumed that God's existence could be proved and discussed as rationally as the phenomena they were investigating in their laboratories. Indeed, Protestant fundamentalists today insist that all biblical statements must be interpreted literally,  so that, if the Bible calls God 'he', this means that God is male.

so that, if the Bible calls God 'he', this means that God is male.

Such fundamentalists are a minority, yet so muddled has religious thinking become in the West that most people probably think that to interpret religious language symbolically is a modern compromise--almost a dilution of faith. They forget that in the ancient world symbolism was part of the essence of religion: the divine was in some profound sense a product of the imagination, rather than a matter of fact. People would create images of God that worked in the same way as a poem or a great piece of music. These images would touch something buried within them and convince them--if only momentarily--that life had some ultimate meaning and value. Often--even in the three monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam--these images of the divine would be female.

In this ancient or ' pre-modern' world, people took it for granted that God or the sacred was never experienced directly but always in something other than itself. Any mundane reality could yield a theophany, if approached with reverent imagination: a place, a rock, a tree, a man or a woman.

Manifestly Divine

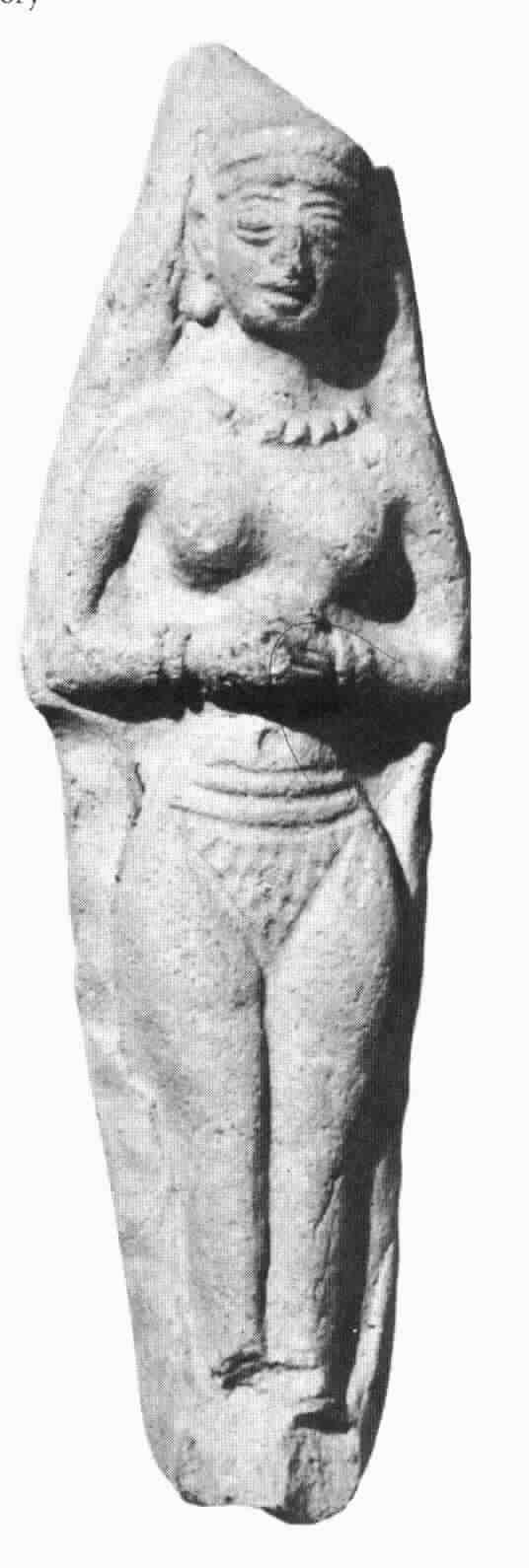

One of the very earliest icons of the divine seems to have been female. In Europe, Asia and the Middle East, hundreds of little figurines, dating from the early Neolithic period, have been unearthed which probably represent the Great Mother Goddess--but scarcely any male effigies from that era have been found. Some of the earliest religious artists instinctively depicted the creator of heaven and earth as a naked, pregnant woman. At this time, when agriculture was just beginning to transform human life, the fertility of the soil was experienced as a sacred force. The earth seemed to produce plants and nourish them rather as a mother gave birth to a child and fed it from her own body.

Later, when human beings created the plough, which penetrated the earth more efficiently, and, later still, began to build cities, more masculine qualities were revered as manifestations of the divine force which kept all things in being. Male gods started to personify the sacred.

But even then people did not forget the Great Mother. She appeared alongside the male deities in the various pantheons of the ancient world: she was Inanna in Mesopotamia, Ishtar in Babylon, Anat or Asherah in Canaan, Isis in Egypt, and Aphrodite in Greece. She was still revered as the source of life and, since there can be no life without death, she was also the Lady of the Underworld. In the ceremonies symbolising these spiritual truths, women served as priests as a matter of course, as the earthly representatives of the Great Mother.

But even then people did not forget the Great Mother. She appeared alongside the male deities in the various pantheons of the ancient world: she was Inanna in Mesopotamia, Ishtar in Babylon, Anat or Asherah in Canaan, Isis in Egypt, and Aphrodite in Greece. She was still revered as the source of life and, since there can be no life without death, she was also the Lady of the Underworld. In the ceremonies symbolising these spiritual truths, women served as priests as a matter of course, as the earthly representatives of the Great Mother.

Polytheism, the worship of many gods, constantly reminded the faithful that the divine could never be confined to any one human expression. The mystery which underlay the fragilities of life was pictured in gods and goddesses who resembled human beings, images that expressed a sense of affinity with the sacred. However mysterious and even frightening it might be, the divine was still in basic sympathy with humans in their ceaseless fight to survive in this frequently terrible world.

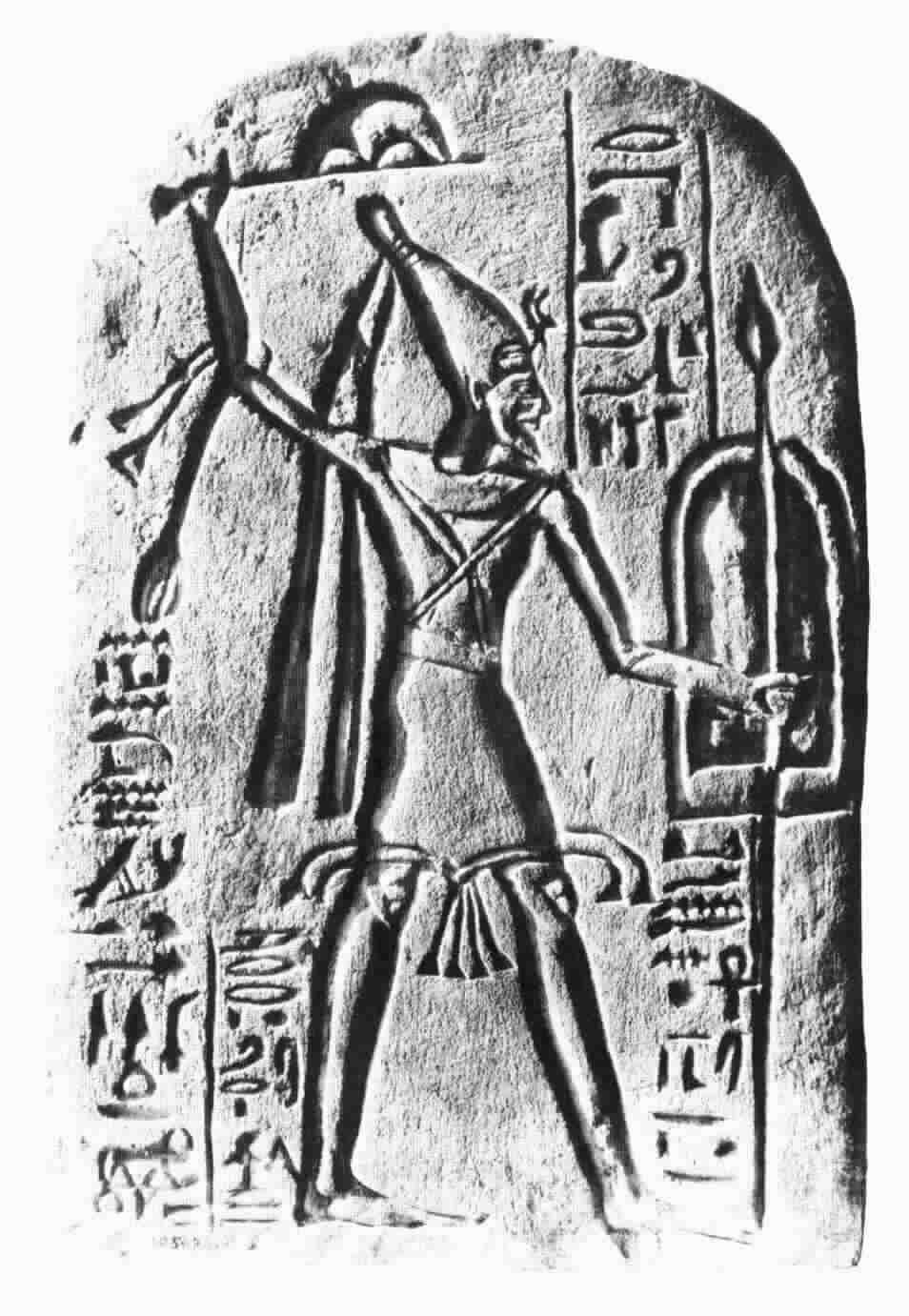

In this process the goddesses were just as militant as the male deities. It was Anat, for example, not her consort Baal, the storm god of Canaan, who overcame Mot, the Lord of death and sterility. The story showed her cleaving him with her sword, winnowing and grinding him like corn, and finally sowing these fragments in the ground. The female was seen as potent, not passive, and just as capable as the male in the constant attempt to bring new life out of darkness and death. These stories were never regarded as historically factual. Rather, they expressed truths that were too profound and elusive to be recounted in any other way than poetry and fiction.

Manifestly One

Such a many-faceted vision of the sacred is still preserved in Hinduism. Monotheism, however, would permit only one symbol of the divine. There was always, therefore, the possibility that its vision would be more limited--a risk against which creative monotheists were on guard. One of their difficulties, however, was that the god of the Jews, Christians and Muslims began as an incorrigibly male deity.

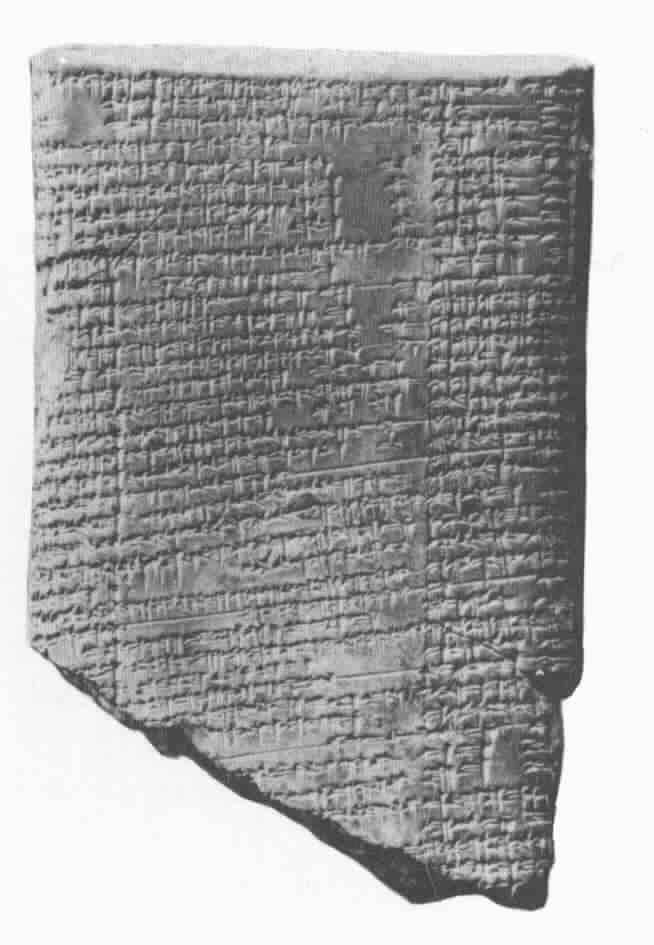

The God of Moses was a god of war. He was Yahweh Sabaoth--'Yahweh of Armies'. Murderously partial, he sided with his own people, the Israelites, but drowned the entire Egyptian army in the Sea of Reeds and ordered the extermination of the native population of Canaan, the land he had promised to Israel.

The God of Moses was a god of war. He was Yahweh Sabaoth--'Yahweh of Armies'. Murderously partial, he sided with his own people, the Israelites, but drowned the entire Egyptian army in the Sea of Reeds and ordered the extermination of the native population of Canaan, the land he had promised to Israel.

This tribal deity was later revered as the creator of heaven and earth, the source of law and justice, and the most powerful of all the gods. He jealously demanded that the people of Israel bind themselves by a covenant to worship him alone.

Early Israelite religion was not, however, monotheistic: the Israelites believed in the existence of other deities but professed an allegiance to one particular god. In the ancient world this was somewhat eccentric. Why neglect other cults, which had long been powerful sources of help and inspiration? The Bible shows that most of the Israelites continued to worship the gods and goddesses of Canaan alongside Yahweh, until they were deported to Babylon in the 6th century BC.

For example, we know from the prophecy of Hosea that the cult of Baal was popular: Israelites celebrated his reunion with his sister and consort Anat in sacred sexual rites, which, they believed, would bring the divine fertility to the earth. They would commemorate Baal's capture by Mot, Anat's search for him, her anguished wanderings through a blighted world--parched without Baal's rains--and, finally, her victory over Mot which brought new life to the world. Israelite prophets abhorred these pagan devotions but for most of the people they proved irresistible.

For example, we know from the prophecy of Hosea that the cult of Baal was popular: Israelites celebrated his reunion with his sister and consort Anat in sacred sexual rites, which, they believed, would bring the divine fertility to the earth. They would commemorate Baal's capture by Mot, Anat's search for him, her anguished wanderings through a blighted world--parched without Baal's rains--and, finally, her victory over Mot which brought new life to the world. Israelite prophets abhorred these pagan devotions but for most of the people they proved irresistible.

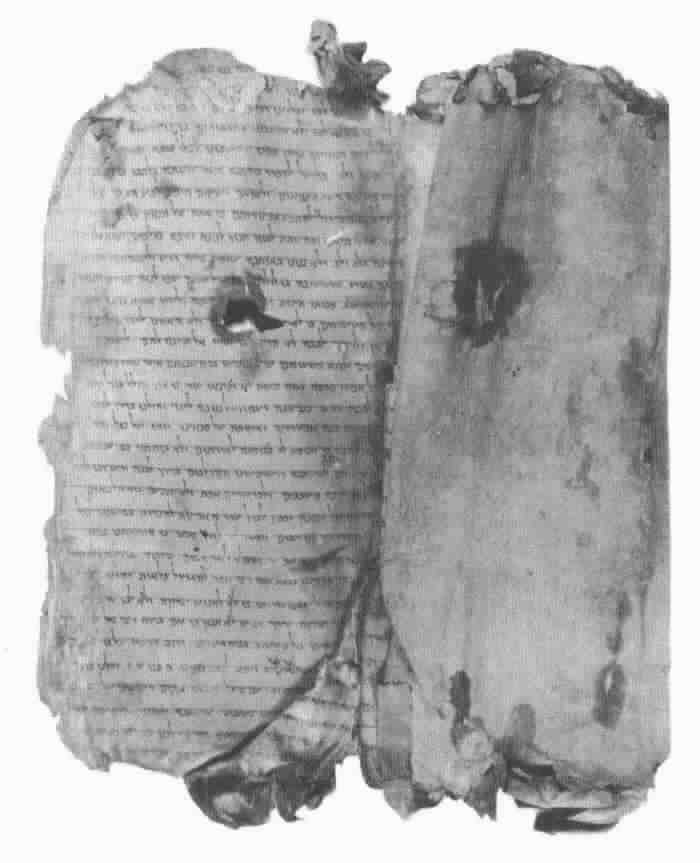

Other Israelites were devoted to Asherah, the consort of El, the old Canaanite high god. Her cult as Great Mother was celebrated in the Jerusalem temple until its destruction by Nebuchadnezzar in 586BC. There were dormitories for her sacred prostitutes in the temple, 'where women wove garments for Asherah' (2 Kings 23:7). Some Israelites seem to have thought that she was Yahweh's consort: witness the inscriptions to 'Yahweh and his Asherah'. The prophet Jeremiah also tells us that Israelites worshipped the Syrian goddess Ishtar, Queen of Heaven (Jeremiah 7:18), and that after the destruction of Jerusalem he was blamed for the catastrophe, because he had lured the people from her (ibid, 44:15-19).

The destruction of Jerusalem and the exile of the Israelites to Babylon put paid to their cult of the goddess. In exile, prophets and priests shaped the new religion of Judaism, fiercely monotheistic in its denial of any other god or goddess. The irascible Yahweh became a symbol of compassion and utter transcendence, above all human categories and conceptions:

For my thoughts are not your thoughts, my ways not your ways--it is Yahweh who speaks. Yes, the heavens are as high above earth as my ways are above your ways, my thoughts above your thoughts. (Isaiah 55:8,9).

One of those transcended categories was sexual identity. Because God could never be conceived in bodily form, the use of all images in his cult was forbidden; any human expression of the divine was so limited that it was potentially blasphemous.

But, though it was possible to rid temples and synagogues of their effigies, to expunge people's mental pictures of God was another matter. The Bible's description of Yahweh Sabaoth made it all too easy for worshippers to see their God as a male being. Yet monotheists still felt the lure of female icons of the sacred and tried to balance the biblical imagery by introducing feminine imagery into their theology. In the Book of Proverbs (composed in the 2nd century BC), God's wisdom, by which he created the world, is depicted as female (8:20-31). The divine attribute through which God expresses himself in the material world is thus a feminine presence to balance the masculine creator of Genesis.

Basic Impulse

Humans are always drawn to images of wholeness. Much of the religious quest can be seen as a search for a harmony that was supposedly the original and proper condition of humanity. Nearly all cultures evoke a 'Golden Age' at the beginning of time, when men and women were at one with one another, with the natural world and with the gods. In the biblical story of Eden, the man and the woman were at first 'not ashamed' of the sexual difference between them. One consequence of their fall from grace was an imbalance between the sexes. The woman would always yearn for her husband, but he would merely dominate her (Genesis 3:16).

Humans are always drawn to images of wholeness. Much of the religious quest can be seen as a search for a harmony that was supposedly the original and proper condition of humanity. Nearly all cultures evoke a 'Golden Age' at the beginning of time, when men and women were at one with one another, with the natural world and with the gods. In the biblical story of Eden, the man and the woman were at first 'not ashamed' of the sexual difference between them. One consequence of their fall from grace was an imbalance between the sexes. The woman would always yearn for her husband, but he would merely dominate her (Genesis 3:16).

In many cultures, the imagery of sexual union has symbolized the integration of warring opposites. Similarly, in their conception of the divine, monotheists tried to rectify the sexual imbalance of their tradition in order to evoke the sense of wholeness that is invariably associated with the sacred.

Perhaps the most audacious attempt is found in the Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition. Since the Talmudic age, Jews had spoken spoken of God's presence in the world as his Shekinah (from the Hebrew shakan, to pitch one's tent). It was a way of emphasizing the transcendence of the divine essence which is utterly inaccessible to us. The Shekinah is, as it were, an afterglow of God, not God himself. Or herself. By the 12th century AD, Jewish mystics had started to regard the Shekinah, the 'divine presence' that is closest to humanity, as female. Later, in the 16th century, Kabbalists developed a myth that spoke of a primal catastrophe in the divine sphere at the beginning of time, when the earliest harmony was lost. Sparks of divinity fell to the world and were trapped in matter. After the sin of Adam, the Shekinah went into exile from the rest of the Godhead and wandered through the world, lost and yearning for her divine Source.

The prophets of Israel had tried to eradicate the old pagan mythology. Now the Kabbalists revived the ancient tales of the goddess who, like Anat, wandered through the world, exiled from the divine sphere. Kabbalists believed that by observing the commandments they could end the exile of the Shekinah.

They devised ceremonies on Friday nights to celebrate her reunion with the Godhead as a marriage ritual. Tales of divine copulation, rejected by the prophets as blasphemous, were integrated into the monotheistic vision as images of healing and unity. At a time when Jews were experiencing exile from the Promised Land as a dangerous condition, especially in Europe, they found consolation in this vision of restoration and unity. This type of Kabbalah was embraced eagerly by Jews from Persia to England, from Germany to Poland, as well as in North Africa and the Yemen.

Christians, meanwhile, had not only inherited the martial God of Moses but believed that this God had become incarnate in a male human being. Yet they too developed a counterbalance through the cult of the Virgin Mary. Officially, theologians have insisted that Mary is a mere mortal, but in the imagination of many ordinary Christians the Mother of God has been a substitute for the Great Mother. The Greek Orthodox have always seen salvation less as a forgiveness of sin than as a process of 'deification' (theosis), whereby human beings become, like Christ, permeated by divinity. As the first and most perfectly redeemed Christian, Mary is thus a prototype of this divinised humanity.

The cult of Mary, becoming popular in the 12th century, at the time of the Crusades, satisfied a desire for a less macho Christianity. Yahweh Sabaoth, whose authorization of divine wrath may have spurred the Crusaders' massacre of Jews and Muslims, was balanced by a gentler presence. 'O clement, O loving, O sweet Virgin Mary,' ends the hymn attributed to St Bernard, who summoned the Second Crusade. All over Europe, great cathedrals dedicated to Mary expressed this alternative vision. Instead of taking Jerusalem by slaughter and bloodshed, Christians could build their own holy places at home.

The cult of Mary, becoming popular in the 12th century, at the time of the Crusades, satisfied a desire for a less macho Christianity. Yahweh Sabaoth, whose authorization of divine wrath may have spurred the Crusaders' massacre of Jews and Muslims, was balanced by a gentler presence. 'O clement, O loving, O sweet Virgin Mary,' ends the hymn attributed to St Bernard, who summoned the Second Crusade. All over Europe, great cathedrals dedicated to Mary expressed this alternative vision. Instead of taking Jerusalem by slaughter and bloodshed, Christians could build their own holy places at home.

Muslims are reminded that God embraces both sexes each time they read the Koran. Each recitation begins with the bismallah: 'In the name of Allah, the Compassionate (al-Rahman), the Merciful (al-Rahim).' Allah, which in Arabic simply means 'The God', is masculine in grammatical gender, but al-Rahman and al-Rahim are etymologically related to the word for 'womb'.

Muslim theologians have followed this lead. Shias revere the person of Fatimah, Muhammad's daughter and mother of the line of inspired imams who embodied the divine truth for their generation. As such, Fatimah is associated with Sophia, the divine wisdom, which gives birth to all knowledge of God. She has thus become another symbolic equivalent of the Great Mother. But Sunni Islam has also drawn inspiration from the female.

The philosopher Muid ad-Din ibn al-Arabi (1165-1240) saw a young girl in Mecca surrounded by light and realized that, for him, she was an incarnation of the divine Sophia. He believed that women were the most potent icons of the sacred, because they inspired a love in men which must ultimately be directed to God, the only true object of love. At about the same time, Dante had a similar experience in Florence, when he saw Beatrice Portinari as an image of divine love.

Muslims are reminded in the Koran that humans can experience and speak about God only in symbols. Everything in the world is a sign (aya) of God; so women can also be a revelation of the divine. Ibn al-Arabi argued that humans have a duty to create theophanies for themselves, by means of the creative imagination that pierces the imperfect exterior of mundane reality and glimpses the divine within. Jean-Paul Sartre defined the imagination as the ability to think of what is not present.

Imagination must be a religious faculty, since it enables people to envisage the eternally absent and elusive God. Creative monotheists have associated female images, redolent of peace and healing, with the sacred. Perhaps this type of spirituality can counteract the cruelty and hatred that monotheism has so often been party to and that can perhaps be traced back to the warlike--and masculine--God of Moses. If so, let God (rather than 'the Lord') be praised.

© 1996 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved; 21-Dec-96